All too often, Santeria is mistakenly confused with other African-derived magical or religious systems. It is very common for people to refer to the practices of Santería Lucumi (Lukumi) as “voodoo” by the media, in television and cinema. Movies and television are notorious for lumping all African Diasporic Traditions into one boat, calling them all voodoo and then mocking them or creating sensationalism that is rooted in cultural misinformation. Tack on to this cross-confusion between Voodoo and Hoodoo and you get a whole other layer of misunderstanding about what Santeria really is. We hope this article will help clarify some confusions, and help set the record straight once and for all.

Santeria and Voodoo are often confused for one another

Both Santeria and Voodoo are religions but they are not the same thing. Let’s begin with an explanation of Voodoo. First, Voodoo is more properly spelled Vodou or Vodoun. There are two main branches to Vodou, Haitian Vodou and Louisiana (or New Orleans) Vodoun.

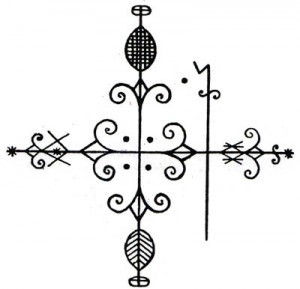

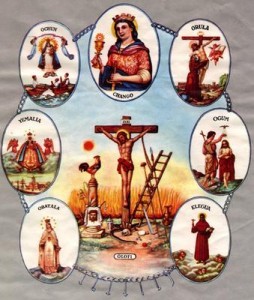

Haitian Vodou is an African Diasporic Religion that came together from the traditional African religious practices of several tribes, some of whom were rivals forced to survive and depend on one another under the conditions of slavery. These tribes included the Fon, Yoruba, Congo and even elements of the native Taino population that survived in Haiti. These people united their practices in an effort to survive, and created a “regleman” (ritual order) to honor and give each tribe’s spirits their moment of worship. These practices were also influenced through syncretism with French Catholicism. Evidence of this can be seen in the use of Catholic saint images to represent the Lwa (spirits) honored in Vodou. The Lwa (spirits) of Vodou are composed of the Rada Lwa (the vudu and orishas of the Fon and Yoruba people), the Petwo Lwa (the fiery spirits of the Congo, the Taino and modern-Haitian people) and the Gede Lwa (the spirits of the dead). Veves, ornate cornmeal drawings laid out on the ground or on tables, are used to call the Lwa in Vodou, but not in Santeria. Haitian Vodou does have an initiated priesthood, but initiation is not a requirement for participation in the religion and the vast majority of vodouisants are non-initiates. Magical wanga and gris-gris are often used in Haitian Vodou’s magic. Haitian Vodou’s primary liturgical language is Kreyol, the local dialect of Haitian French.

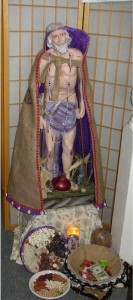

A typical Haitian Vodou altar. Compare this to the photo below of a Santeria altar and note the differences. Photo by Jeremy Burgins.

Louisiana Vodoun is markedly different from Haitian Vodou. It is more of an amalgamation of religious and magical practices found in the southern United States. This includes some of the Lwa found in Haitian Vodou, a strong presence of the Catholic Saints, and elements of southern folk magic like gris-gris, wanga and mojo bags. There is not a “regleman” in the same manner as Haitian Vodou and there is more of an emphasis on self-made Vodou Queens like the famous Marie Laveau. Louisiana Vodoun has a strong connection with Spiritualism and shares many magical techniques with Hoodoo (southern folk magic) – but should not be confused with Hoodoo. You will see the use of veves (ornate painted symbols) in Louisiana Vodoun, much as in Haitian Vodou. Louisiana Vodoun’s primary liturgical language is English with a bit of French Creole.

Santeria is a religion that evolved in Cuba. It is rooted in the African religious traditions of the Yoruba people (found in modern-day Nigeria). The followers of Santeria worship the orishas, the demi-gods of the Yoruba people. While there is a veneer of Spanish Catholicism for the outsider, that element quickly drops away once a person has undergone initiation. The primary involvement of Catholic elements in Santeria are found in Espiritismo, a separate religious practice that has been deeply interwoven into Santeria as of the mid-1900’s. Santeria is highly initiatory, secretive and operates under strict religious rules. Participation in the religion is very limited to those who are not initiated and the great majority of participants are initiates. Santeria does NOT use veves or ornate drawn symbols to call the orishas as are done in Vodou (bullseye-style paintings called osun are used in certain rituals but bear no resemblance to veves). Santeria’s primary liturgical language is Lukumí, a late 1800’s dialect of the Yoruban language interspersed with elements of Cuban Spanish.

A Santeria altar (throne) to Chango. Each container has a different orisha’s mysteries within it, and is covered with decorative cloths, crowns and beaded mazos. Compare this with the Haitian Vodou altar above.

The religious proceedings and magical workings of these religious traditions may have similarities but they are certainly not the same thing. A person initiated in Santería will not have the religious rights or permission to participate in Vodou ceremonies like a Vodou initiate would. A person initiated in Vodou would not have permission and rights to operate in a Santeria ceremony. Each of these religions is different from one another, and each uses different languages, prayers, songs and rituals from the others. The only commonality between them is the use of animal sacrifice, and the employment of magical spell work as an integral part of their religious practice, but this is common with any religious practice from sub-saharan Africa.

What is Hoodoo? Is it Voodoo?

Often people mistake Hoodoo and Vodou. The differenced between them is simple. Vodou is a religion. Hoodoo is nothing more than Southern Folk Magic. Hoodoo uses the magical techniques of the Congo people of Africa without any of the religion. There is no presence of the nkisi, orishas, or lwa of Africa. In fact, most people who practice Hoodoo are Protestant Christians. You’ll see hoodoo workers also being called rootworkers or conjurers. They make magical charms called mojo bags, or jack balls. They’ll use magical powders, herbal cleansing baths, candles or lamps for spell work. All of this magical work is done while praying Psalms, praying to Jesus and God the Father, and reading from the Bible. While the vast majority of Hoodoo practitioners are Protestant Christians, there are some some Catholic practitioners who will petition Catholic saints. It’s important to note that they are petitioning the Saints themselves, not as a syncretized image for an African deity or spirit. So Hoodoo is not Voodoo.

Stereotypical and Racist Depictions of Santeria and other ATRs

A typical hoodoo altar with several spells being worked for love, reconciliation and wisdom. A hoodoo practitioner will pray Psalms and Christian prayers when they cast spells.

For centuries, the African Traditional Religions (ATRs) have been the victim of racism and colonial stereotypes. This was an institutionalized way of dehumanizing the African people by labeling their religious practices as barbaric or demonic. This changing society’s perception of black people into animals or subhuman, in order to justify the slave trade and the brutal treatment of African people by invading muslim and christian missionaries.

Racist depictions of Santeria and other ATR practices include depicting the religions as satanic. It is common to portray these religions as nothing more than harmful spell casters focusing on zombifying people, using voodoo dolls to harm people, or engaging in cannibalism or pacts with the devil. (It is important to note that the use of dolls in magic comes from European witchcraft traditions.) Satan does not exist in Santeria. Satan is not worshipped in the ATRs. Cannibalism does not exist in Santeria, nor do we shrink heads or any such thing.

Remember when you see depictions like this in movies or television programs, they are racist depictions serving to scare those of European descent by portraying African religions as barbaric. Even the term “black magic” is a racist term. It originates from the labeling of African people as black and the characterization of their religions as purely evil. Therefore “black magic” meant black religious practice was evil. At the Santeria Church of the Orishas we detest the term “black magic” and prefer that people call things what they actually are. When referring to harmful magic call it harmful magic, not “black magic” out of respect for the black people of Africa and their peace-filled beautiful religious practices.

Santeria is Not Evil

Santeria is often mistakenly depicted as an evil religion that worships demons, engages in blood-thirsty rituals and seeks to do evil on others. This is further racist, colonial depiction of the beautiful and complex African religious tradition of Santeria. Santeria’s chief tenet is to always strive to stay in a place of iré (blessings) by following the advice of our egun, orishas and elders. There is a strong ethic of helping others and working cooperatively to lift people out of poverty and sickness toward blessings, health, prosperity and longevity. We pray for “iré omó, iré owó, iré arikú babawa” which means “blessings of children, blessings of prosperity and blessings of long life.” We strive to cultivate a good character, live peaceful lives and respect nature and others around us. There is the use of magic for one’s defense, but in many ways this is no different than praying to God for defense against your enemies or petitioning saints to stop those who seek to harm you. The same thing can be said for other ATRs like Vodou, Candomblé, Arará, etc.

The problem is lack of understanding and lack of knowledge. As long as people accept racist stereotypes and don’t educate themselves about the African Traditional Religions, they will continue to fear Santeria. The Santeria Church of the Orishas actively works toward demystifying Santeria Lucumí through educational efforts, so that people will know and understand what we actually believe and what we actually do.

Pagan Blog Project

Pagan Blog Project

Follow Us!