Pumpkins are a very important ebó when someone receives the odu Obara Meji. They are a gift for Oshún and Changó to bring prosperity.

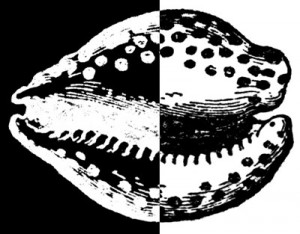

Obara meji (6-6) is a powerful and complex odu within diloggún and Ifá divination that can teach us much about our power as olorishas. This beautiful odu teaches us about the power of our words, the importance of our legacy that we leave behind and our own purpose in life. Whether you have this odu in your itá, or if you receive this in a reading, or if you are just a student of odu, this sign can show you how to cultivate your power as a priest.

The King Does Not Lie

In the odu Obara Meji we say “The King Does Not Lie”. This is an odu of royalty, and this sign indicates that the person being read with the shells is of a regal nature. But being a king does not mean you get to boss everyone around – as tempting as that may be. Royalty is not just about ancestry, it is about cultivating the proper manner of conduct and recognizing what it takes to lead people.

A simple trek through any history book teaches us about good monarchs and corrupt ones. Kings, being given a divine right to rule, are often unchecked, untrained leaders who run amok. If they are a malevolent, ill-tempered and volatile king who lashes out at anyone who challenges his rule, they are hated by their people and become the focus of bloody revolutions. However, if they are benevolent, even tempered, receptive and responsive to the needs of their people, they will stay firmly seated on their throne of power for their entire lives (as will their descendants).

This sign teaches us that to be a good leader, one must be honest, forthright and have integrity. To live up to the royal inheritance this sign promises we must learn that honesty is the cornerstone of power; and the more one lives an honest life the more power one’s words have in the ears of those around them.

But just as power can cut both ways, so too can honesty be a knife that cuts the wielder and the victim. Honesty must be delivered with tact. Tact is the sheath that keeps honesty from hurting everyone around you. Delivering truth in gentle and non-offensive ways is the mark of a good leader. Hiding truth behind lies or a resentful holding of the truth to avoid confrontation, however, is the mark of weakness. The king does not lie, and so we must learn to deliver the truth as a loving parent would to his children, without anger and without vengeful bitterness.

He Who Knows Doesn’t Die Like He Who Doesn’t Know

Lying is forbidden in the odu Obara Meji. It kills the power of a person’s word and those very lies can manifest into reality.

This famous saying is well-known by olorishas, aborishas and aleyos in Santeria. Many times it is said as an adage to remind us all that knowledge is power and to be forewarned is to be forearmed. Obara Meji teaches us that in order to survive we must know the ways of the world, the nature of our true self, and the path to destiny.

Divination gives us a glimpse of our path toward destiny. It is Eleggua orienting us and letting us know where we are in our path, what lies immediately ahead, and how to prevent any calamities through ebó. In ebó there is a solution to bring us back into the graces of iré, but most people forget that ebó had two parts to it: sacrifice and behavior modification. While sacrifice does give us a spiritual technology to dramatically alter the flow of ashé in our lives and give us the lift we need to overcome obstacles and osogbo, it is behavioral modification that prevents us from falling back into the patterns that caused that osogbo in the first place.

As a diviner, I’ve found that clients are too focused on things they have to do, versus on the kind of a person they need to be. There is more power and positivity to be found in following the behavioral restrictions, the taboos and the advise that odu gives us than just in the act of offering fruit to the orishas or taking a ritual bath. Yes, the offerings and rituals are important too, but they are in vain if you are unwilling to make the change within yourself after your consultation with diloggún.

He who knows doesn’t die, like he who doesn’t know. Obara Meji teaches us that knowledge is the key to our survival. Not only does divination forewarn us against our pitfalls that lead to osogbo, but so too does knowledge of self. In this sign, understanding one’s own weaknesses and strengths is critical. Weaknesses should be something we actively work on overcoming, healing and cultivating into strengths. Yet it is often our strengths, perverted by neurotic behavior that manifest as our weaknesses. For example, if you are incredibly well spoken (and Obara Meji does signal someone with a fast tongue) that may be a strength, until those fast-flung insults and quips start flying in a moment of anger. Now your strength of being a good speaker has become a weakness of being a rude and insulting jerk. Understanding the nature of your weaknesses is half the battle, and Obara Meji teaches us that it can save our very lives.

With Your Tongue You Can Save Or Destroy The Village

In Obara Meji we say that the client’s tongue (or speech) has lots of power. We say that the tongue can save or destroy a village, and we would be well served to remember this when we are under this odu’s influence. We often forget the power and influence that our words have over others. An innocent, but poorly-timed quip can utterly destroy a person’s self-esteem or ruin an event. Similarly, a well-timed and crafted word of encouragement can lift up a person’s spirit or even save a village. This is the power of Obara Meji.

We are well served to remember the power of the tongue when we are under the influence of Obara Meji. We can utilize this power to our advantage if we are crafty, intelligent and strategic. Our powers will manifest into reality, and as such anything we speak WILL BE! We can speak affirmations and positive goals when under the influence of Obara Meji knowing that this odu’s power will manifest them. We should avoid speaking negative comments, insults, curses and lies because our tongue’s ashé under this sign will make them be so. Remember that controlling the tongue is the key to succeeding under this sign. Use the tongue’s power for constructive ends and you will ride Obara Meji’s power to the benefit of all.

This is just a cursory exploration of Obara Meji but it is something every priest needs to keep in mind. Our ashé is seated on our heads, but manifests through our words and actions. Remember it is our actions that become the legacy we leave behind. We should all work to leave behind a legacy of constructive deeds, good character and positive memories that our descendants would recall us with fond memories and praise our names for generations.

Pagan Blog Project

Pagan Blog Project

Follow Us!